Learning Game Design: Game Elements to Consider

The game elements you choose to include in your game should be carefully selected, with a focus on making the play experience fun and facilitating/enhancing the learning experience. In last week’s post I introduced game elements as a whole, and provided a more in-depth description of conflict, cooperation/competition, and strategy/chance. This week’s post focuses on the next four game elements to consider when developing your learning games: aesthetics, theme, story, and resources—with time considered to be a fairly significant resource.

Aesthetics

Aesthetics, or visuals, are one means of engaging players and helping to immerse them into the game experience. In video games, aesthetics are a huge part of the game experience. Even board games rely on aesthetics to pull players in, as well as to offer visual cues that guide game play. With learning games, however, the temptation can be to cut corners on aesthetics and not realize the impact this has on the learning value of the game. If you are a one-person band, you may simply say, “Well, I don’t have a graphic designer to help me.”

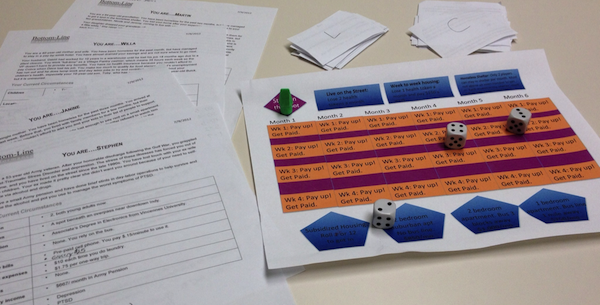

Compare these two game boards, for example. Which one would you rather play?

If you have no budget for a graphic designer, there are online resources for helping with aesthetics. Here’s a couple to check out:

http://opengameart.org — has some nice graphics bundles you can download and use in your digital games.

http://elearningtemplates.com/elearning-activities/ — has cutout people and graphics as well as some “game” templates (they aren’t really games, but are gamified activities.)

Theme

A theme can add interest and create engagement. In the game Forbidden Island, the theme is conveyed through the visuals and a “back story” that is included in the rules. There is no narrative running through the game, but the back story and the aesthetics convey the theme of a mythical, mystical island. Knowledge Guru uses thematic elements to convey the idea of theme even though there is no real story.

When creating a learning game, ask yourself whether a theme can enhance the learning experience and create interest for the learner.

Story

Story offers a narrative thread that pulls through an entire game. It’s far easier to remember facts when they are part of a narrative, rather than when we simply have the facts devoid of any “story” or context around them. A game can have a theme but no story, a theme and a story, or no story and no theme (think Scrabble). If you elect to create a storyline for your game, keep in mind that a strong story has four elements:

- Characters

- Plot (something has to happen for it to be a story)

- Tension (often thought of as conflict)

- Resolution

Example: We’re working on a game story right now that uses the theme of an alien invasion. We have a detailed story to go with it. Players have to successfully demonstrate knowledge of incident investigation to thwart the aliens and rescue their fellow workers. Our story has characters: the player who represents a worker, a learning agent who represents an expert cohort, and the Martians who have invaded with Dr. E.L. Snatcher as their leader. It has a plot: an invasion has happened, workers have been captured. It has a conflict: Martians against the human workers. And it has resolution: the resolution comes if the player can successfully use knowledge of incident investigation and rescue all his co-workers.

Notice how the images below help evoke emotion and interest in the story itself—hence, the relationship between story and aesthetics.

Questions to ask yourself as a learning game designer:

- Should I use a story?

- Should I couple my story with a theme?

- Will it help my game or make it too complicated?

- How much story do I need?

- Do I need just enough story to convey a theme? Or do I need to immerse players in the story to provide the right learning experience?

- Example: The stories used in Settlers of Catan or Forbidden Island are really “back stories” used to set up the game. The story doesn’t drive the game itself. This contrasts with some of the intense video games.

- How do I integrate story?

- Do I make each player a separate character?

- If so, who do they represent? Is it a fantasy character or does it represent something with real-world context to their job or situation?

Resources

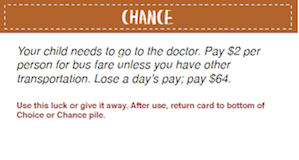

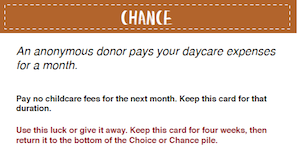

Resources are often defined as part of game mechanics, but they are the tools the player has available within the game to help them achieve the goal. Common resources include money, tools, building materials, etc. In the game of Monopoly, resources include money, real estate, houses, and hotels. All have value within the game and all contribute to helping a player win. In Settlers of Catan, players very literally have cards called resources. These include sheep, ore, wheat, and bricks. Players can use resource to purchase buildings or Development Cards, or they can trade for other resources.

When designing a learning game you should ask yourself:

- What resources make sense given the skill or knowledge you’re trying to teach?

- Do I need to include currency to represent something, or would that be a distractor?

- Do you need resources in your game? (Perhaps not.)

- Do you want to incorporate time: time can be a resource, it can be a constraint (e.g. you have to complete a task within a specified amount of time), or it can be a means of compressing real-world time into a more manageable amount of game time.

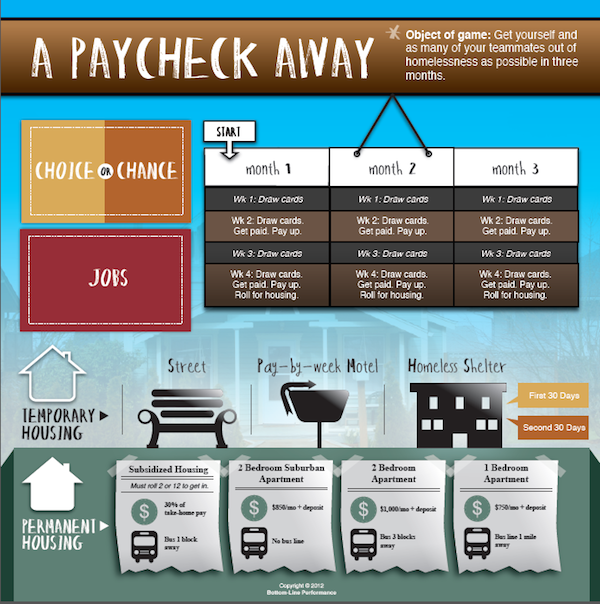

- Example: In A Paycheck Away, we compress three months of homelessness into a 90-minute game play experience.

- If I want to incorporate time, do I want to use it as a resource, a constraint, or a means of compression?

- Example: In Knowledge Guru, time is not a factor at all. We originally designed it as a constraint—giving players two minutes to complete a round of play—and we found out that this actually detracted from the game play rather than enhancing it. Consequently we eliminated it.

Sharon Boller, President of BLP and lead designer of Knowledge Guru, will be a regular contributor on this blog. She’ll be kicking things off with a Game Based Learning blog series inspired by her experience designing digital and tabletop learning games for our clients.

Sharon Boller, President of BLP and lead designer of Knowledge Guru, will be a regular contributor on this blog. She’ll be kicking things off with a Game Based Learning blog series inspired by her experience designing digital and tabletop learning games for our clients.