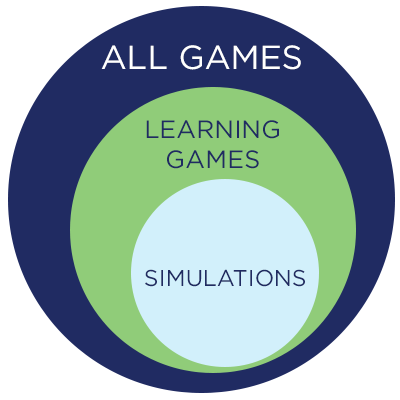

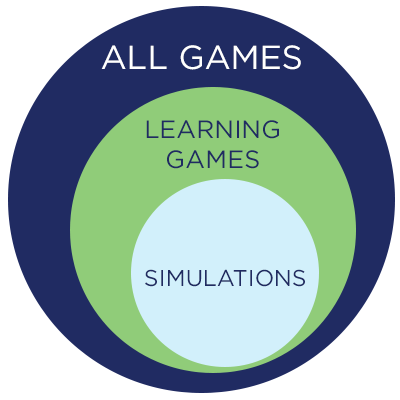

The word “game” is a big one… and it really refers to a category of activities that can look many ways. There is some natural confusion that arises around this topic, particularly on the difference between games, simulations, and gamification. I’ll focus on games and simulations in this post.

Here’s the definition I always give when asked to define what I mean by game:

An activity that has an explicit goal or challenge, rules that guide achievement of the goal, interactivity with either other players or the game environment (or both), and feedback mechanisms that give clear cues as to how well or poorly you are performing. It results in a quantifiable outcome (you win/you lose, you hit the target, etc). Usually, it generates an emotional reaction in players.

Categorizing Learning Games and Simulations

With the definition in hand, we can then think of how we might sub-categorize the word “game.”

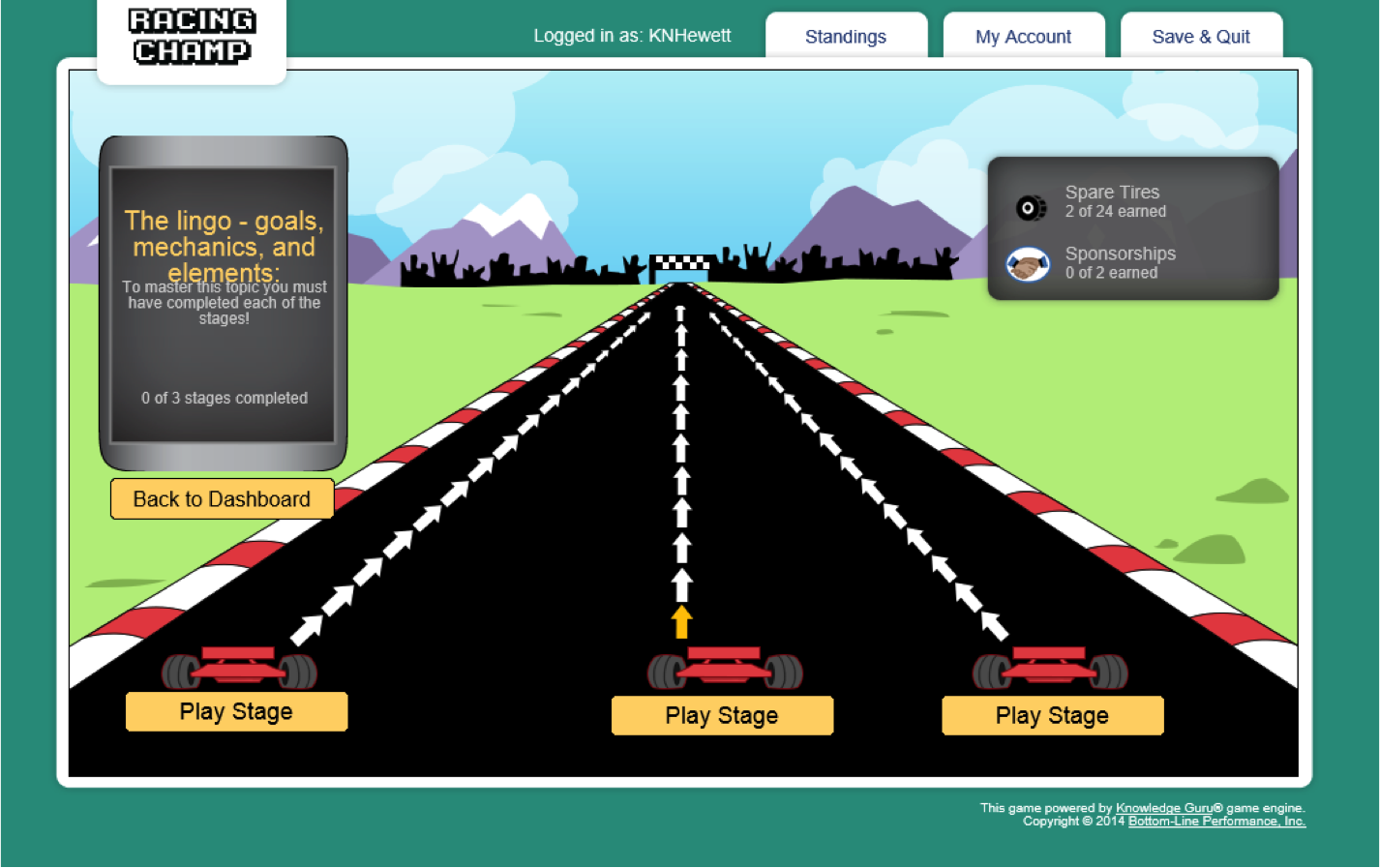

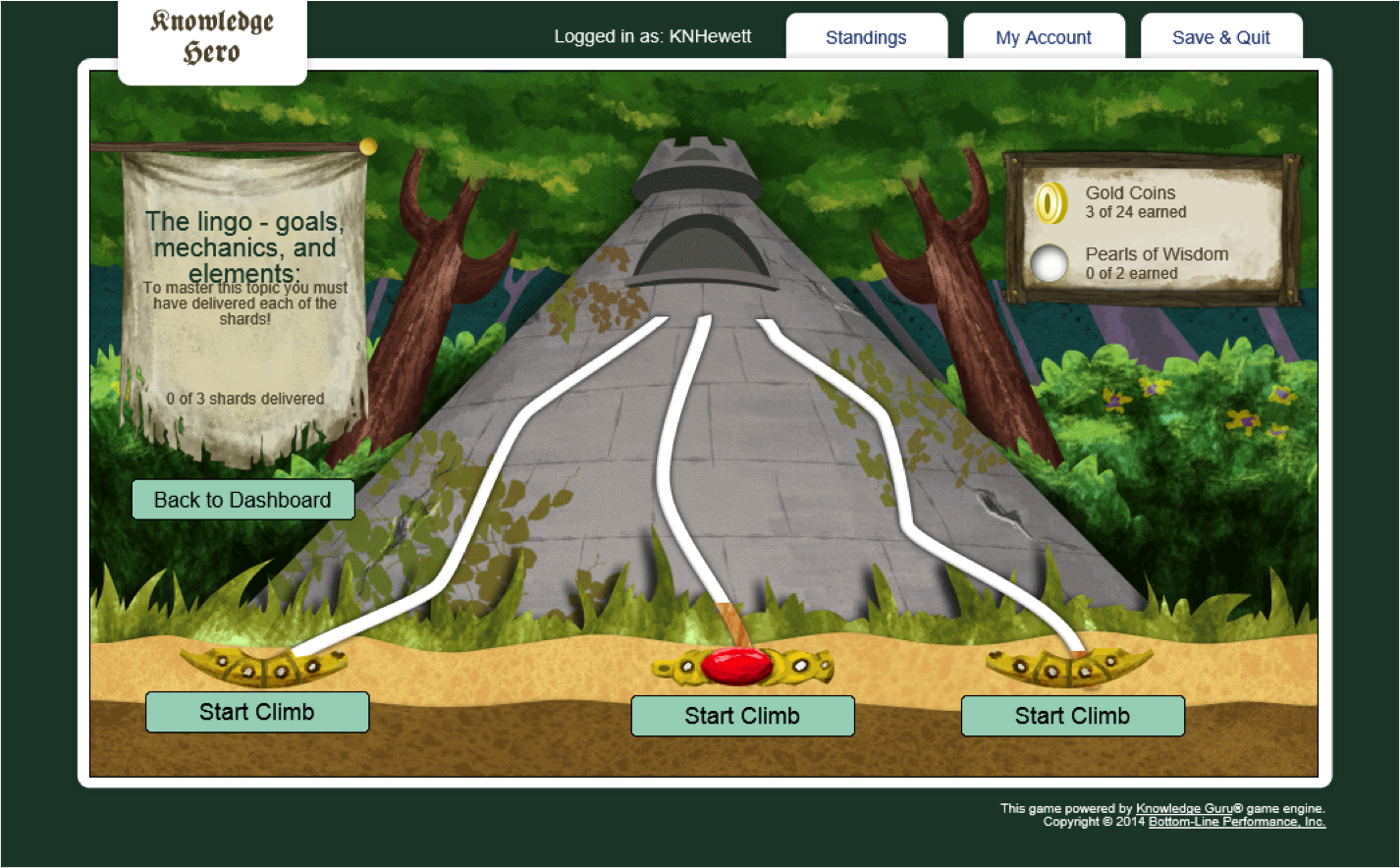

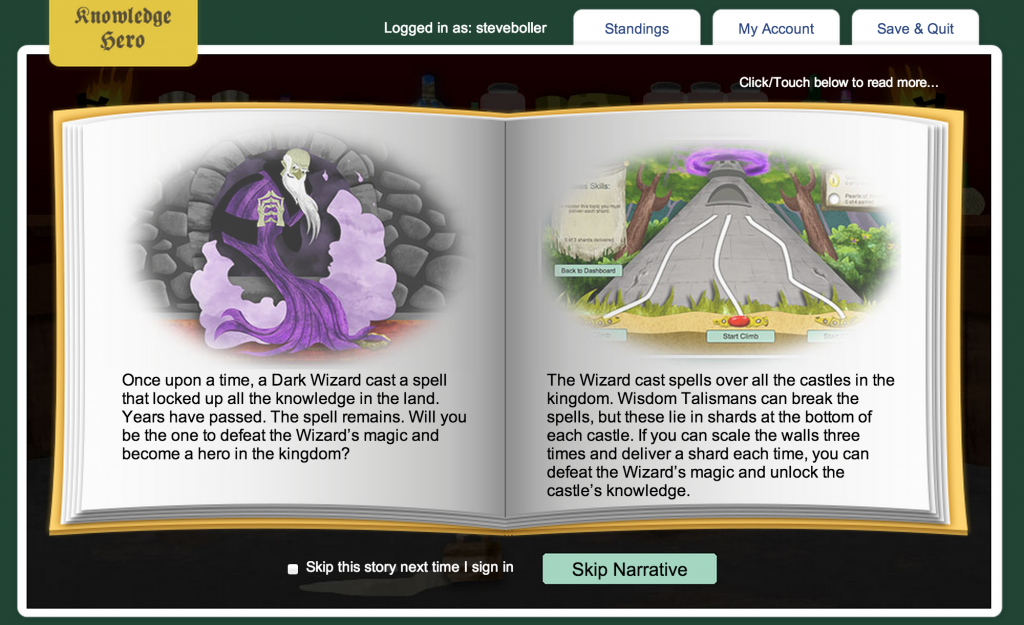

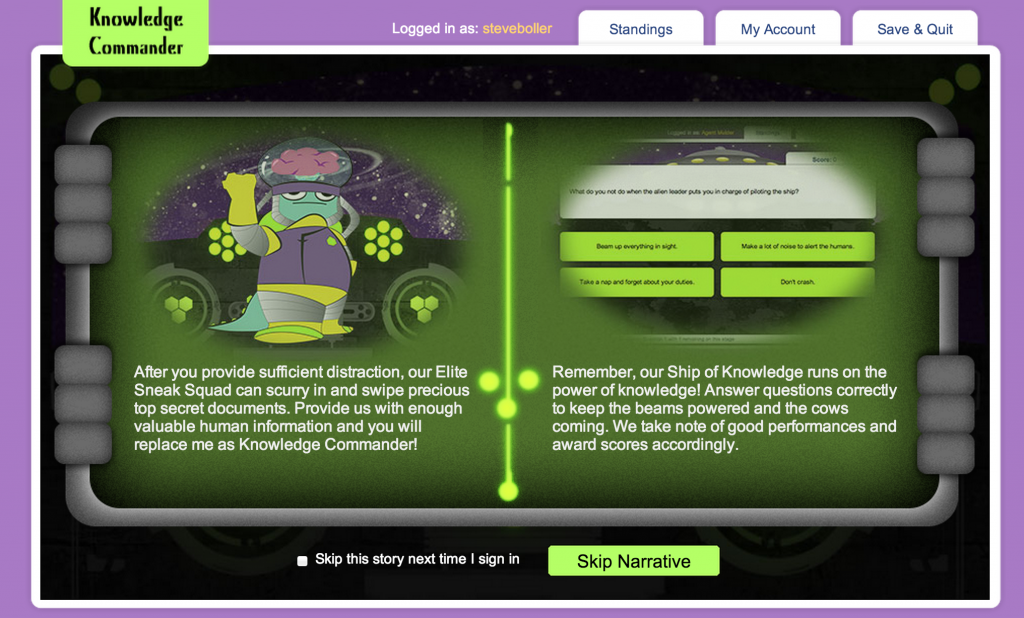

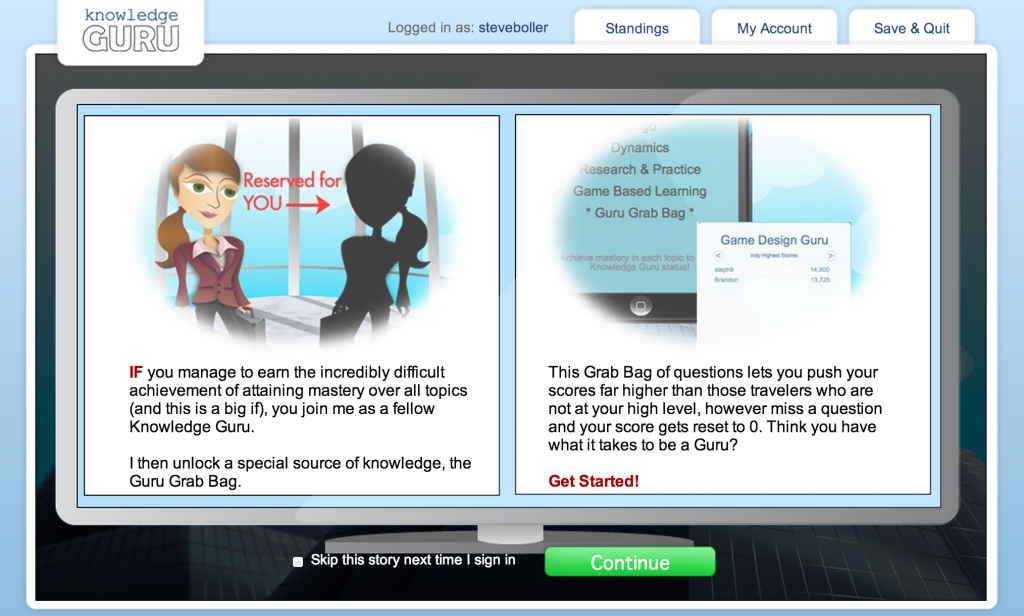

Within the classification of games, you have a subset labeled “learning games” or “serious games.” Games created with the explicit intent of helping someone learn a specific set of knowledge or skills belong in this category. On the education front, you have things such as Treasure Math Storm, Oregon Trail, and Where in the World Is Carmen San Diego. In the corporate world, an example would be our Knowledge Guru platform. We’ve also designed card games, mobile games, computer games, and board games to help people learn new knowledge or skills or to reinforce knowledge or skill learned via other means.

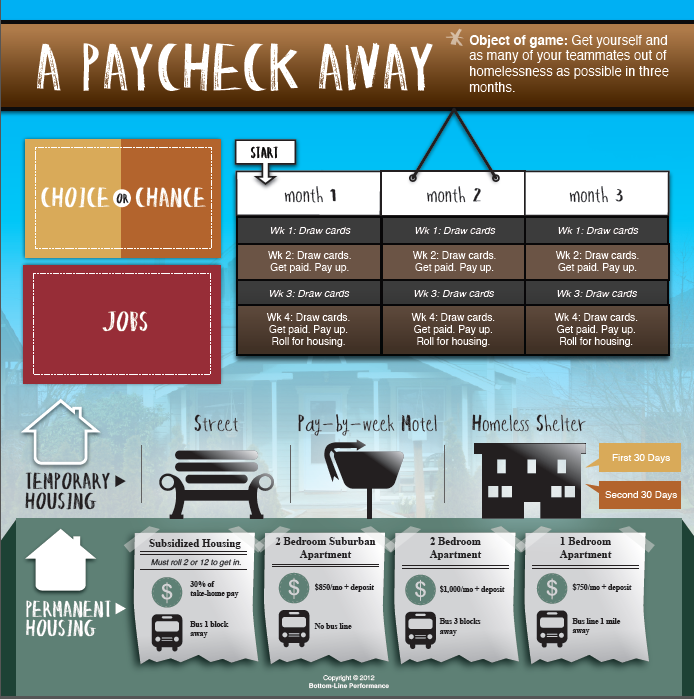

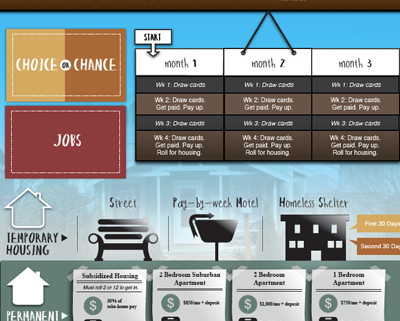

Then we’ve designed simulations—sometimes we design them to be games, and sometimes not. Simulations can be designed as games, but they don’t have to be. (Confusing, isn’t it?) A simulation is a re-creation of a situation you could encounter that requires you to problem-solve and make decisions that mimic what you would have to do in the real-world. Simulations provide a safe means of practice when practicing in a real-world situation would be either too costly or harmful. (e.g. No one practices flying in a real jet. You learn first in a simulator.)

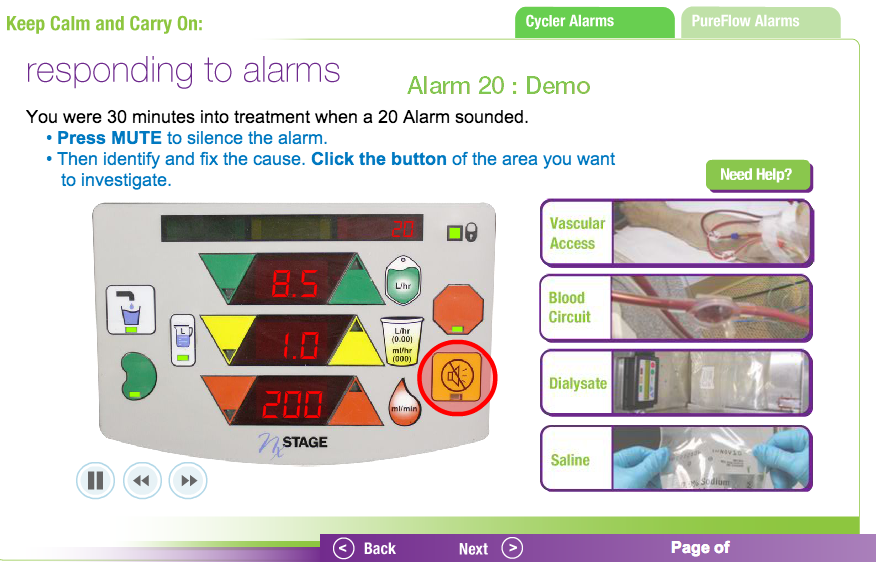

An Example of a Simulation

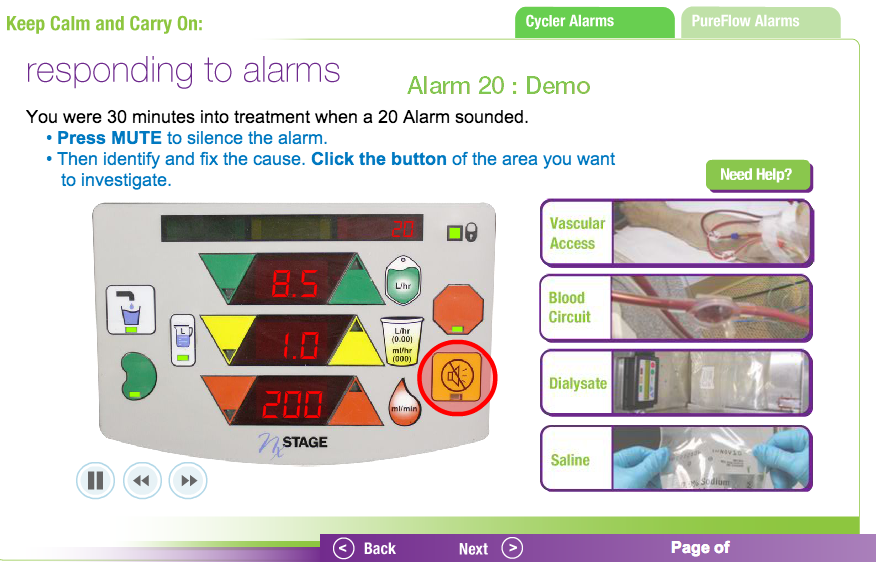

Here’s an example of a simulation we created that is not a game. The learning goal was for patients to be able to respond to common troubleshooting alarms when doing home hemodialysis, and then safely resolve the alarm. Here are some screen grabs of the simulation with notes about what we did:

The image shown above is the actual face of the dialysis equipment. The learner will practice resolving “Alarm 20,” which is an actual alarm that can go off during treatment. They get a situation cue: “You were 30 minutes into your treatment when a 20 Alarm sounds.” We set this simulation up with levels so the patient can be guided through resolving the alarm the first time. In this novice level, the patient practices with a lot of guidance. The red circle shown here prompts them to turn the alarm sound off and the options to the right offer possible causes of the alarm.

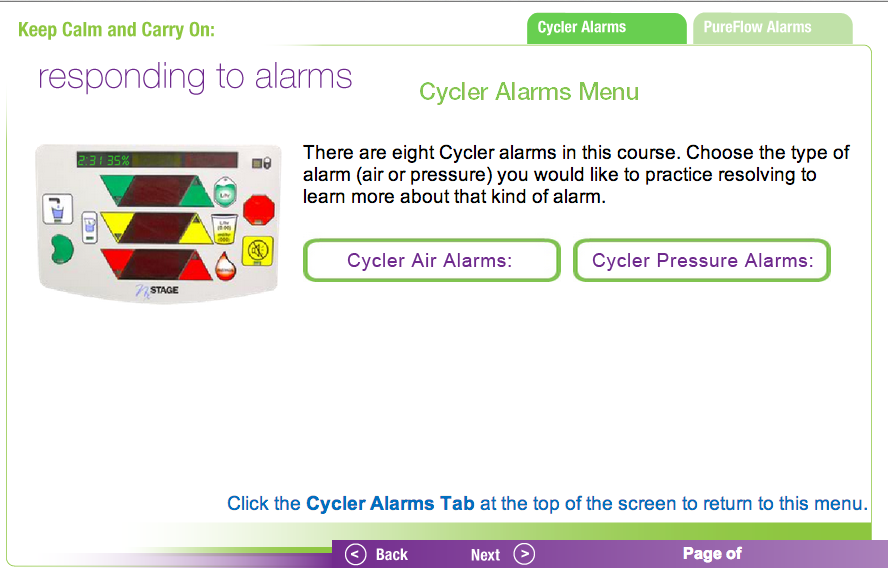

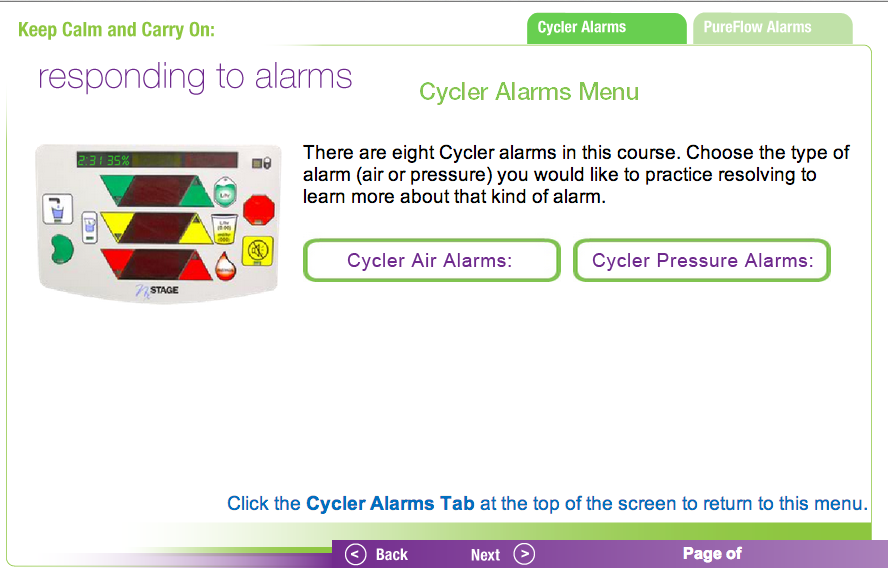

Once they go through the demonstration level, they come to a screen that simply lets them choose what they want to practice.

The screen above looks very similar to the novice level. They once again get a situation prompt: “You started treatment about 3 minutes ago and just finishing resolving a Check for Aterial Air 11 alarm when the Cycler started sounding again. This time you need to resolve Alarm 10.”

The big difference, however, is that there is no red circle pointing out where to start or what to do.

Simulations contain many game elements

For instance, simulations can:

- Have levels of difficulty just like games do

- Be graphically rich

- Provide a lot of feedback regarding how you are doing.

- Present as a challenge that you have to resolve.

- Generate a lot of emotion within the participant.

When simulations are not designed as a game, the thing that typically keeps them from meeting the full-fledged definition is the fact that there is no explicit win/lose state. In the dialysis example, there is no scoring and the learner is not trying to “win.” They are also not competing against anyone else or cooperating in order to beat the computer opponent.

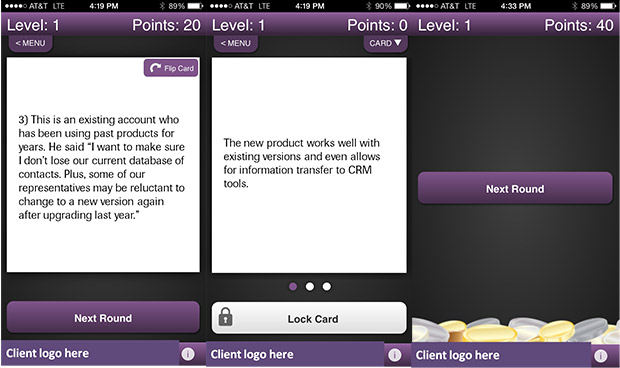

An Example of a Game

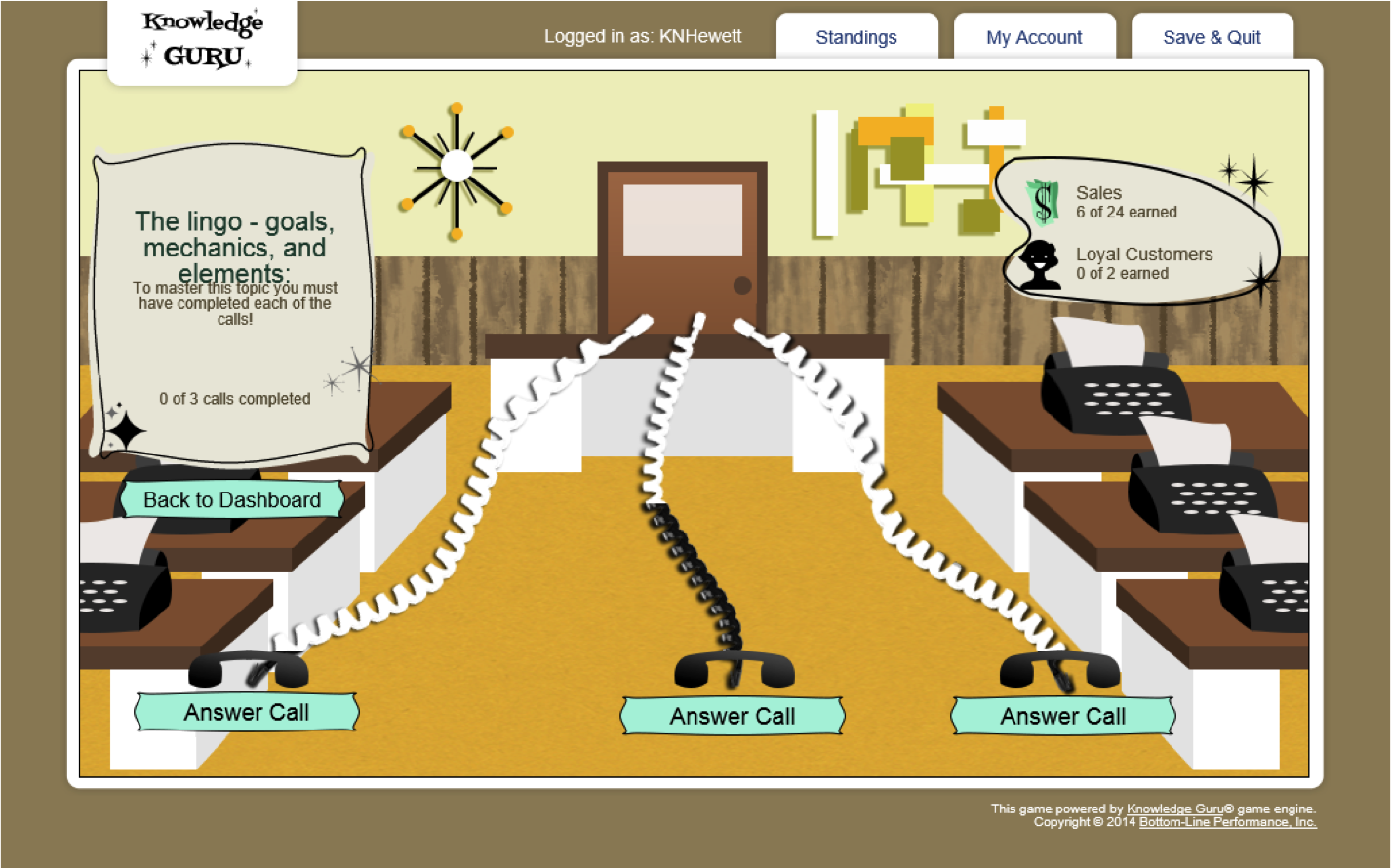

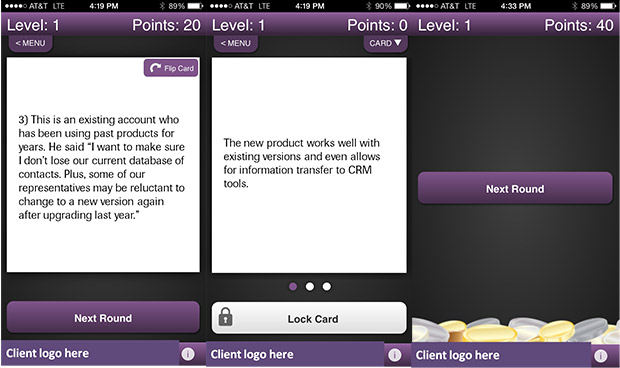

Is a simulation the “holy grail” of learning games? Are simulations the best way to do learning? Not always. Here’s a mobile game we designed to help sales reps get ready to work directly with customers in selling a new software product. It definitely helps them practice positioning features and benefits of a product… but it is not simulating their real-world environment. They play it in a workshop around a table. Here are three side-by-side screenshots of the smartphone app:

You play this game like Apples to Apples. There is a Round Master who takes the role of a customer. He presents a challenge to the other players, which is an objection or a question. The Round Master can view the optimal response to the situation by tapping FLIP CARD. The other players have access (on their phones) to a variety of responses they could offer. They choose the response card they want and tap LOCK CARD to select it. They must then present this response to the Round Master as though he or she was the actual customer. The Round Master gets to score the response based on how well it matches the optimal response and how well they delivered it. The player who earns the highest point total wins the game.

This is not a simulation but it does let players practice using their selling skills and knowledge of product messaging. It was a big hit with the target players and a very effective way for them to practice their salesmanship.

Hopefully now you a grasp on the differences and overlaps between simulations and games. This spectrum of engaging learning activities covers a wide range of possibilities for your own training. Use these examples to help evaluate whether your training needs call for a simulation or game, or some blend of the two.