How to Create a Game-Based Learning Strategy

I was speaking with a client the other day. She said only 10% of her workforce completes the training they are supposed to take. In her mind, training completion is low because the content isn’t engaging, and she wanted to know if a learning game could fix it. I told her that there is no “easy button,” and games are not a cure-all for for boring content or bad learning design.

Game-based learning can improve learner engagement, but only if you start with a strategy. Years of research shows that game-based learning can increase not only learner engagement, but drive both higher retention and completion rates. Industry professionals are now spending less time debating what the research says about games, but many organizations still struggle to correctly implement games that drive meaningful results. Adding a learning game to the mix just to ‘jazz things up’ could be like putting a Band-Aid on the problem when surgery is really needed.

How do you implement a true game-based learning strategy that will actually work? A strategy where learners actually learn and retain at higher levels? A strategy that drives measurable results?

Here are some key points to keep in mind when creating your strategy:

1. Know your audience

Key stakeholders often get this wrong. I had a seasoned training director tell me that since his audience was mostly women, games just wouldn’t work. Really? According to the Entertainment Software Association, of the 155 million gamers out there, 44% are women. There are marketing games that tout a player demographic of 52% women.

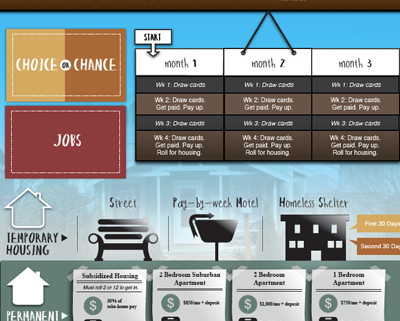

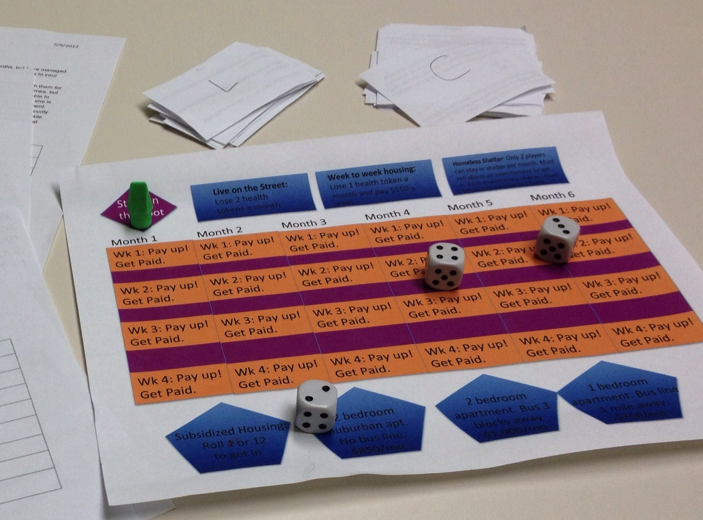

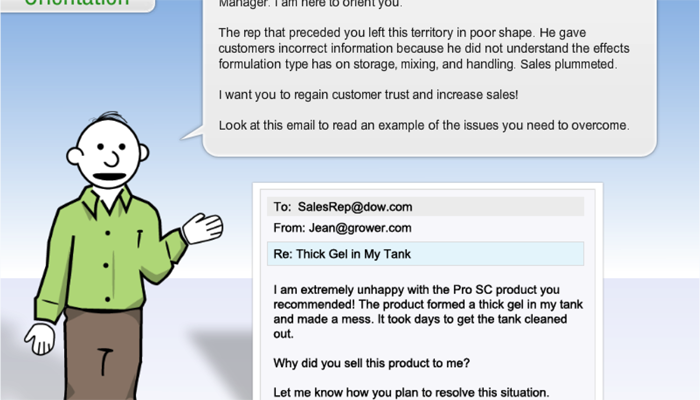

2. Make it relevant

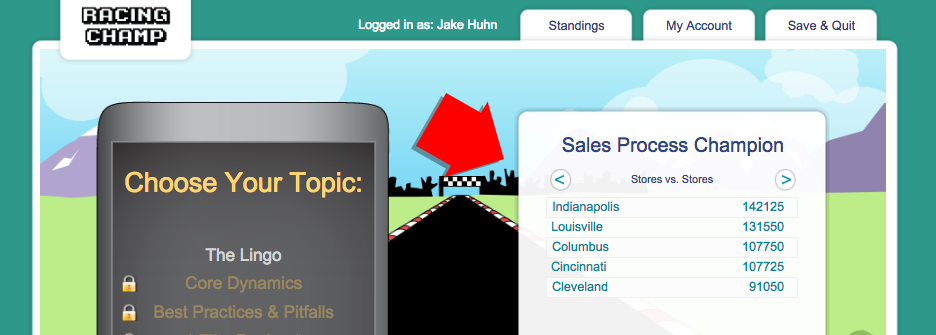

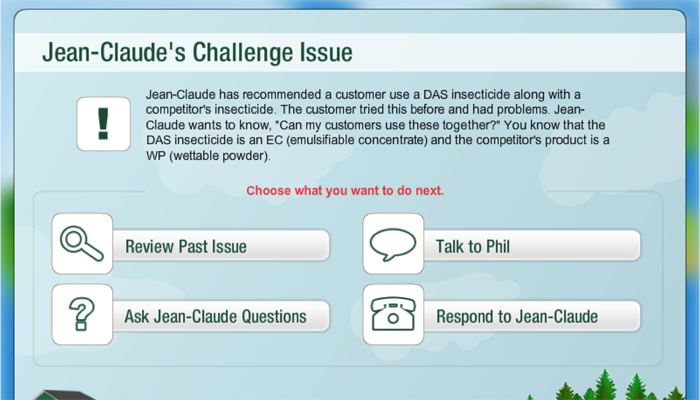

This is where many game-based learning strategies fail. First, learners want activities that are relevant to the learning material and their job. If the game is relevant to helping them retain material or gives them time to practice with material they will use often, then it’s worthwhile. But if it’s not, learners will reject it. If you’ve tried a game before and it wasn’t adopted well by your learners, this might be the culprit. Avoid drawing the conclusion that games won’t work with your learners if this is the case.

3. Make learning the focus

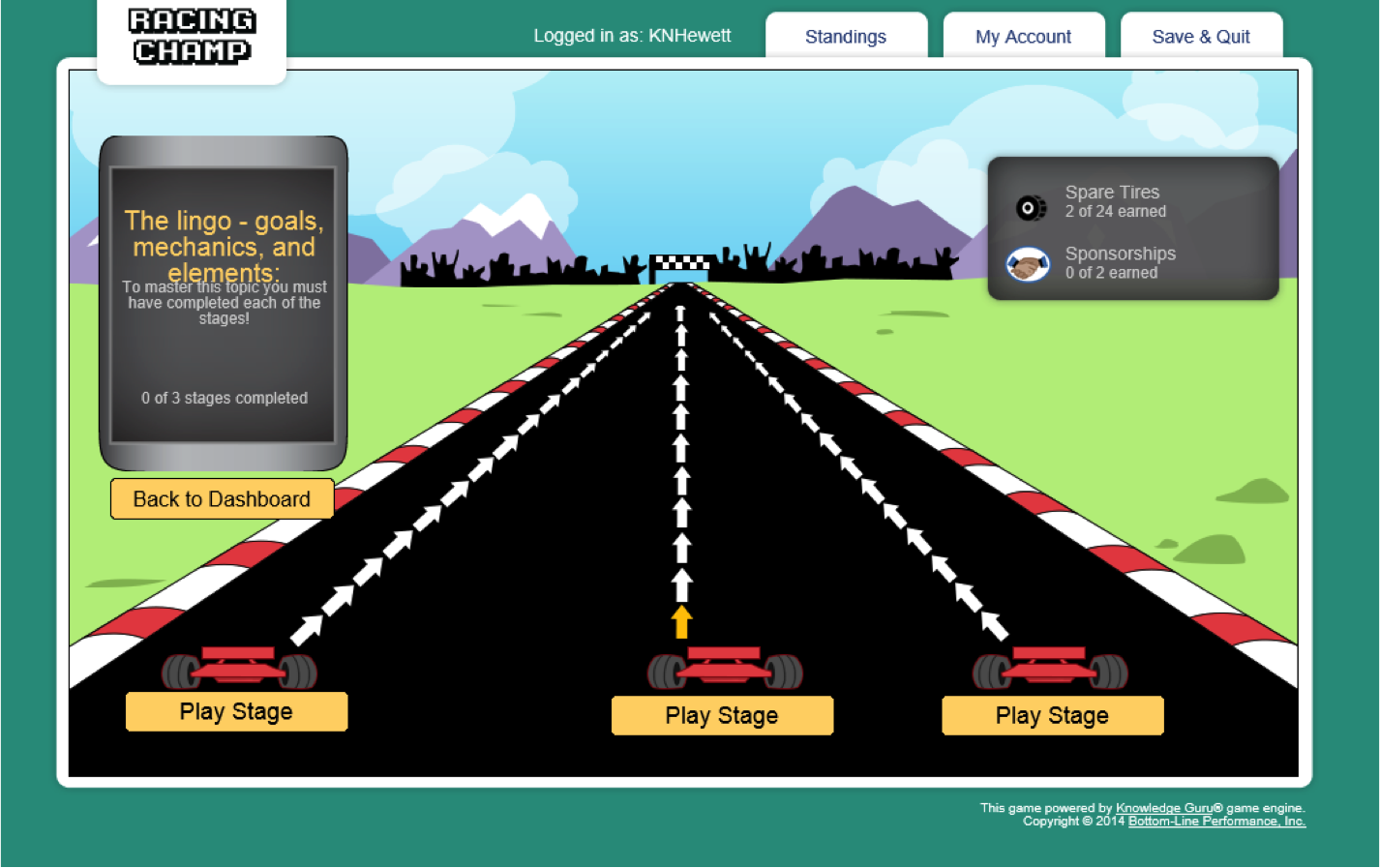

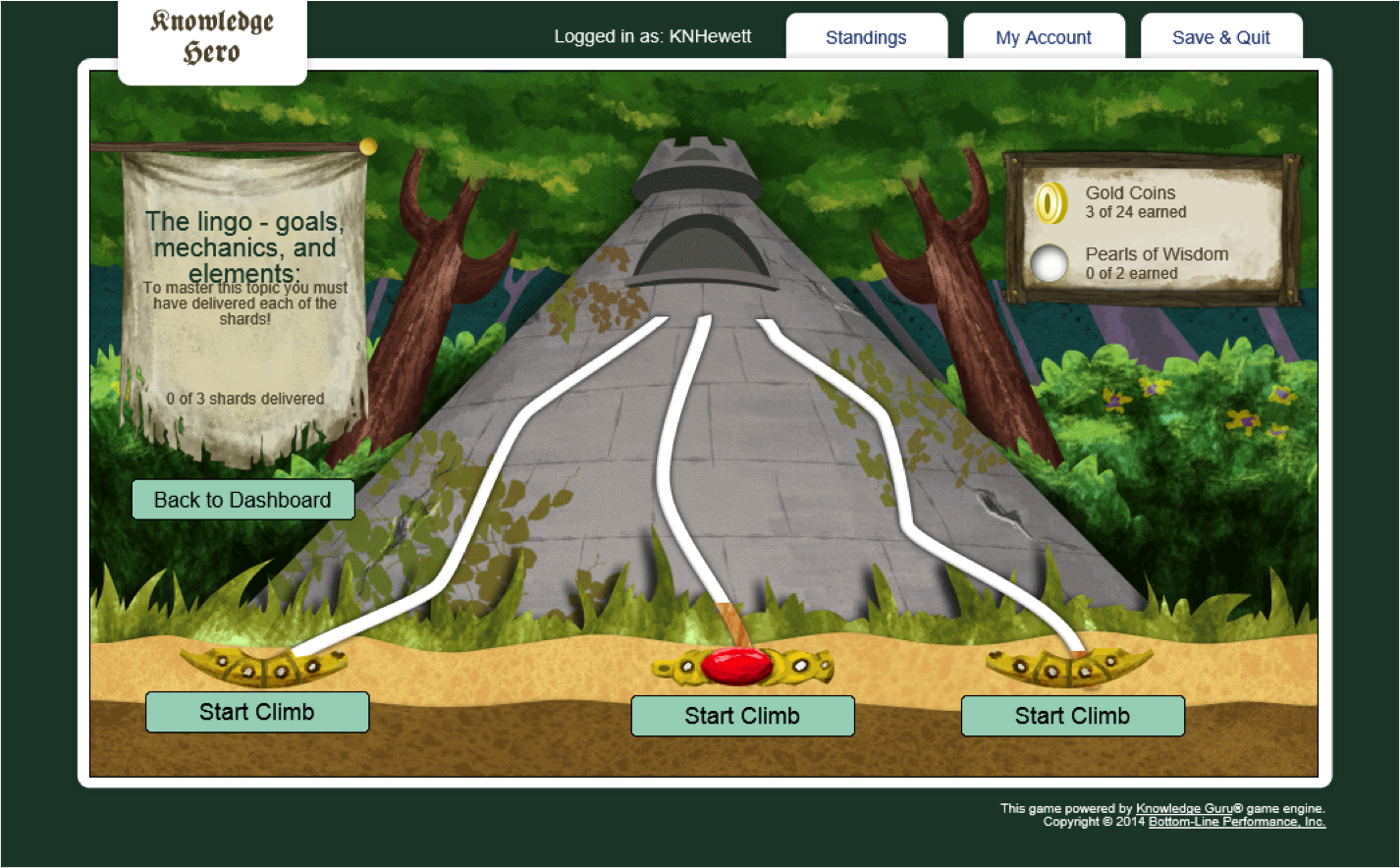

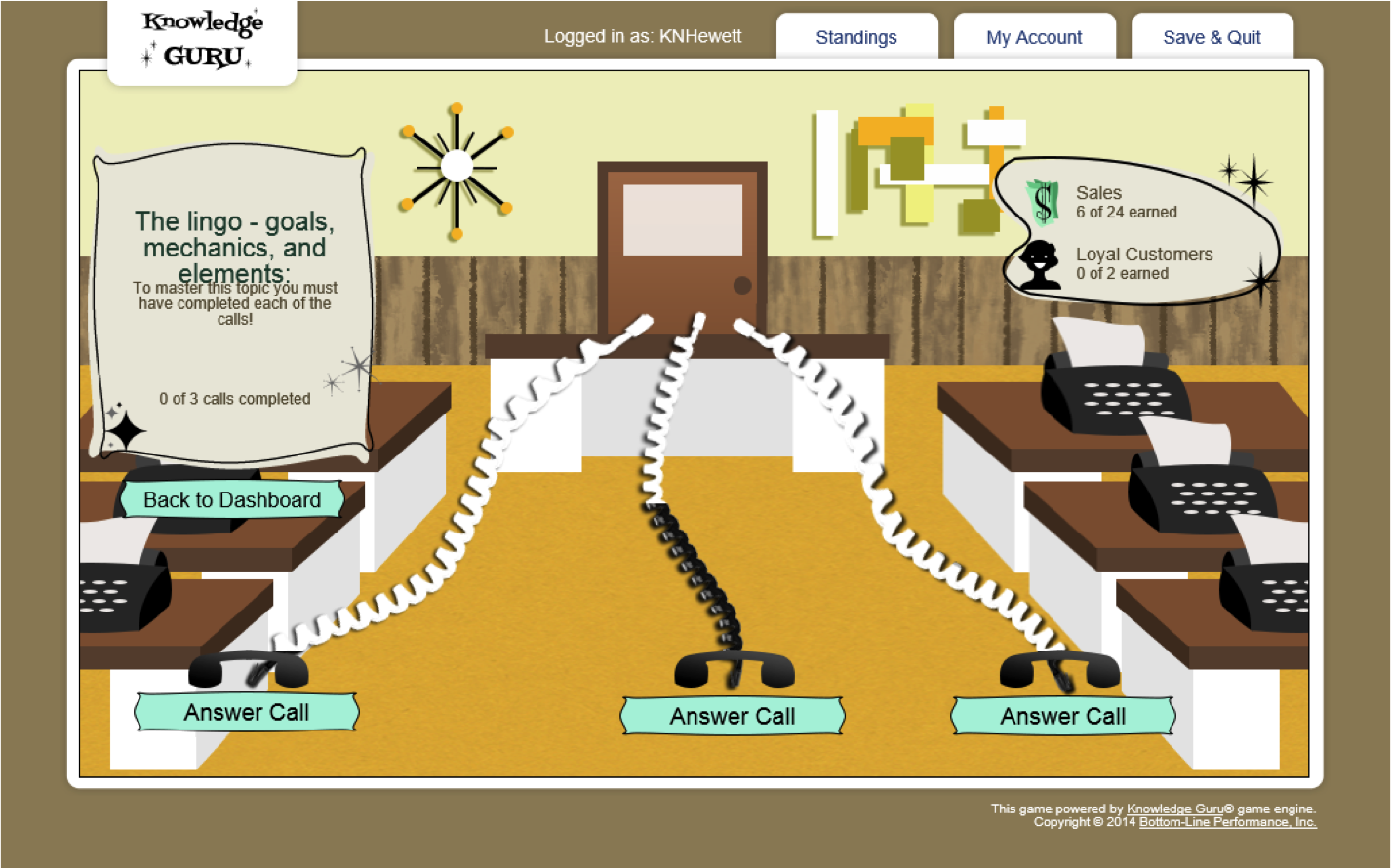

Many folks want serious games to be, well, less “serious.” They want more action, more sound, more addictive qualities to the game. The problem is that the more complex the game design or game-play is, the less cognitive space is left to learn the knowledge and skills you designed the game to teach in the first place.

4. Timing is everything

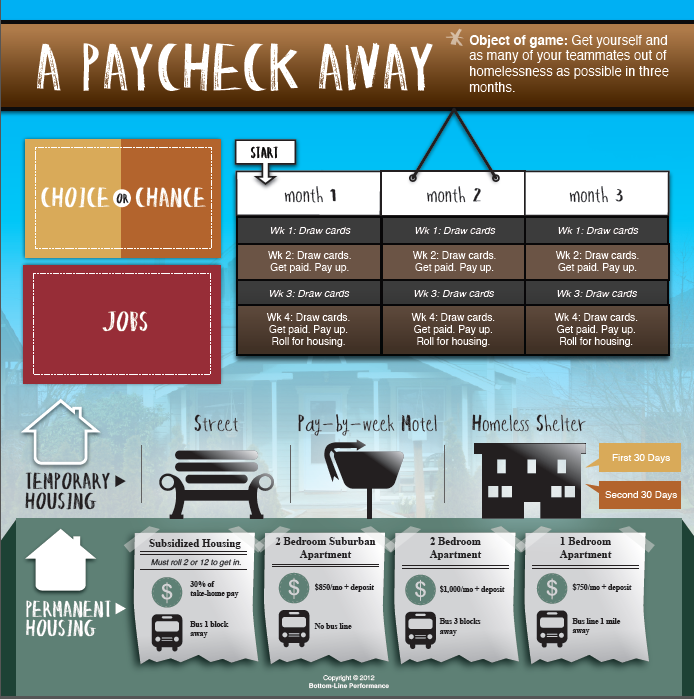

Learning games work best when implemented as part of a blended learning approach. At Bottom-Line Performance, we’ve implemented games as pre-work to a larger training event or instructor-led training as well as post-work for multi-module eLearning curriculums to help learners reinforce what they learned—particularly material they really need to know from memory.

5. Measure the outcomes

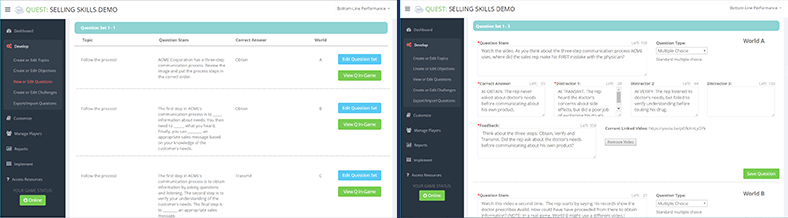

To drive measurable results, you have to know what you want the desired learning outcomes to be and have a way to access the data you need to measure those outcomes. If your LMS reports only completion, choose a platform that can deliver reports detailing how players performed.

Of course, implementing a strategy at your company will involve many more steps than what I have shared here. It will also include testing to gauge the response a game-based learning approach has with your learners. Whatever your desired business outcomes are, make sure your game-based approach is based on sound instructional design.

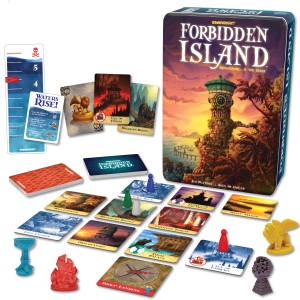

Last weekend, I was with friends and I introduced them to the game

Last weekend, I was with friends and I introduced them to the game