6 Must-Read Learning Game Design Books

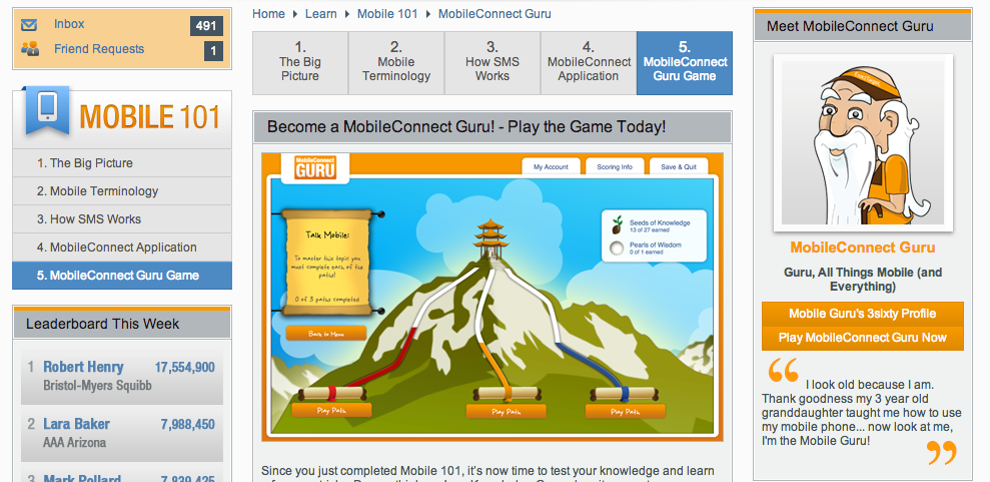

Designing a game is no easy task, but do you know what’s even more difficult? Designing a game that helps people actually learn something. The BLP team (creators of Knowledge Guru) is no stranger to the challenges that come with learning game creation. That’s why we read about it! We constantly study the research and stay up to date on the latest game-based learning and gamification trends.

Here are six learning game design books that are on our must-read list:

Play to Learn: Everything You Need to Know About Designing Effective Learning Games

By Sharon Boller & Karl Kapp

As a trainer interested in game design, you know that games are more effective than lectures. You’ve seen firsthand how immersive games hold learners’ interest, helping them explore new skills and experience different points of view. But how do you become the Milton Bradley of learning games? Play to Learn is here to help.

This book bridges the gap between instructional design and game design; it’s written to grow your game literacy and strengthen crucial game design skills. Bottom-Line Performance President Sharon Boller and Dr. Karl Kapp share real examples of in-person and online games and offer an online game for you to try as you read. They walk you through evaluating entertainment and learning games, so you can apply the best to your own designs. You can order Play to Learn here.

Actionable Gamification – Beyond Points, Badges, and Leaderboards

By Yu-Kai Chou

This book is a must-read particularly if you’re struggling to connect with and motivate your learners. Rather than teach people how to superficially slap some game elements onto some boring activities, author Yu-Kai Chou takes the reader on a journey that teaches us to uncover why people have different motivations for different behaviors.

The book takes us through his twelve years of obsessive research in creating the gamification framework: Octalysis. He explains how to apply the framework to create engaging and successful experiences in their product, workplace, marketing, and personal lives. Yu-kai provides dozens of fantastic, real-life examples to explain his concepts. You can order a copy here.

The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education

By Karl Kapp

Another great read from the co-author of the first book on our list, Dr. Karl Kapp. In this book, Kapp introduces, defines, and describes the concept of gamification and then dissects several examples of games to determine the elements that provide the most positive results for the players. He explains why these elements are critical to the success of learning. The Gamification of Learning and Instruction is based on solid research and the author includes peer-reviewed results from dozens of studies that offer insights into why game-based thinking and mechanics makes for vigorous learning tools.

Kapp gets practical in this book, too. He discusses how to create a successful game design document and includes a model for managing the entire game and gamification design process. This is definitely a book you want on your bookshelf if you have any interest in learning games or gamification. You can get a copy here.

The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses

By Jesse Schell

This book by Jesse Schell shows that the same basic principles of psychology that work for board games, card games and athletic games also are the keys to making top-quality videogames. Good game design happens when you view your game from many different perspectives or lenses.

“It’s a marvelous tour de force and an essential part of anyone’s game design library.” — Noah Falstein, Gamasutra.com from Game Developer Magazine

Anyone who reads this book will be inspired to become a better game designer – and will understand how to do it. Particularly, if you’re an in-house designer, this book will not only help you work internally with different teams in the company, but also help you address customers and their needs. You can order a copy here.

Challenges for Game Designers: Non-Digital Exercises for Video Game Designers

By Brenda Brathwaite & Ian Schreiber

“Finally! A book that talks about HOW to become a good game designer instead of merely addressing WHAT game design is.” — Amazon Reviewer

That’s only one of a myriad of reasons this book is a must-read for current or aspiring game designers. Beyond being one of the only books to address how to become a good game designer, Challenges for Game Designers stands out by offering hands-on challenges. None of the challenges in the book require any programming or a computer. However, many of the topics in the book feature challenges that can be made into fully functioning games. So if you’re a professional game designer, aspiring designer, or instructor who teaches game design courses, then you should definitely get this book. You can order a copy here.

Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games

By Tracy Fullerton

If you liked the idea of challenges from the previous book, then you’ll love Game Design Workshop by Tracy Fullerton. This book puts you to work in prototyping, playtesting and redesigning your own games. It includes exercises that teach essential design skills. The description even states: “Workshop exercises require no background in programming or artwork, releasing you from the intricacies of electronic game production, so you can develop a working understanding of the essentials of game design.” It’s the perfect book for taking a deep dive into game design and truly learning how to be a great game designer. You can pick up a copy of Game Design Workshop here.

You built a wonderful learning game. So why aren’t you reaping results from it? Before we dive in and diagnose why your learners didn’t learn, grab a piece of real or digital paper. I’m going to ask you to write down things and answer some questions.

You built a wonderful learning game. So why aren’t you reaping results from it? Before we dive in and diagnose why your learners didn’t learn, grab a piece of real or digital paper. I’m going to ask you to write down things and answer some questions.

Last weekend, I was with friends and I introduced them to the game

Last weekend, I was with friends and I introduced them to the game